Project: Carthage Museum Historic Renovation + Byrsa Hill Masterplan Proposal

Year: 2023

Location: Byrsa Hill, Carthage, Tunisia

Team Members: Dinithi Iddawela, Cem Kayatekin, Hirushi Jayasuriya, Mikhail Frantsuzov,

Our understanding of Byrsa Hill and the Acropolium is anchored around the layered historic landscape of the site. Some of these layers are easy to read; others are muddled; and still others are buried. With this proposal, we seek to reactivate the buried, to clarify the muddled, and to start a discussion across the vast and unique historic breadth of the site.

On the scale of the masterplan, this dialogue takes shape through the interplay of two axes. The first, the Roman Cardo-and-Decumanus still visibly cutting through the landscape. The second, another axis derived from the “House of Hannibal.” Throughout the proposal, we mobilize these two axes to engage in negotiation, in discussion, as they push and pull at the various spaces found across the masterplan.

With the spirit of dialogue, discussion, layering in mind, we open up the site to the surrounding city as much as possible. While the museum, the cathedral, and the varying administrative, logistic, and cultural service areas of the proposal can be fully closed during off hours, the broader masterplan is designed to behave as a public park, as a series of public urban plazas linking back to the surrounding urban fabric.

Once-active or already-existing entries to the west, northwest, north, east, southeast, and south are opened up or strengthened. The plaza spaces adjoining these entry points are shaped to support various activities of socialization, recreation, community engagement, and cultural production.

The surrounding ecological fabric is also brought into the site with rigor. Autochthonous landscaping is used not only to shape meaningful public spaces and support the integration of the project into the native landscape, but also as a means of mitigating urban heat island effect, supporting local biodiversity, managing local food waste, as well as managing on-site stormwater via blue-green infrastructural systems.

The interplay of historic layers set in motion at the masterplan, trickles down to the building scale, anchoring the architectural approaches of the proposal. Throughout the work, we intervene minimally, but meaningfully. New interventions are used in a focused, strategic manner, seeking to amplify and add new voices to the existing capacities and poetics of the buildings on site.

From Princess Dido to the Punic era, we found much of the historico-cultural narratives of Carthage interwoven with maritime exploration. The new architectural interventions of the proposal pay homage to these seafaring chronicles, taking on the material and structural language of lumber boat building. This architectural language framing the new interventions threads in and out of the existing building complex, amplifying specific spaces as needed and carving out entirely new areas for temporary exhibit spaces.

Visible from a distance, these new layers of the site are voices of our contemporary times, building upon the past. They do not try to outcompete the existing complex of buildings atop Byrsa Hill; rather, the new architecture tries to enrich the existing with the addition of a few new critical tones and stories.

In order to minimize its environmental footprint, the project has been shaped around positive-energy district and blue-green infrastructure ideas. The main components of these ideas include: mitigation; building performance; renewable energy generation; and nature-based stormwater, greywater, and food-waste systems.

Autochthonous landscaping is deployed throughout the masterplan and within green roofs in order to mitigate microclimate heat gain (e.g., urban heat island effect) and support local biodiversity. Portions of the landscaping (namely green roofs and bioswales) are used as components of a blue-green infrastructural network geared towards localized stormwater retention, and on-site greywater (not blackwater) remediation. There is also a water plaza placed in UNESCO square, which functions as an emergency stormwater retention basin in times of sudden downpours, while multitasking as a public amphitheater for most of the year when it would be dry.

Composting and vermicomposting modules are embedded in the forested western portions of the masterplan. These module arrays allow for the biodegradable waste of the museum complex to be fully disposed of locally, while also offering the local community workshops on how this can be done at smaller scales.

The insulation levels and envelope airtightness of existing buildings would be upgraded throughout the renovation of the complex. Passive shading devices (e.g., lightshelves) would be implemented around windows and doorways to reduce the exposure of internal thermal mass to solar gains. To reduce carbon footprints, demolition of existing buildings was kept to a bare minimum. And where it could not be avoided, the new buildings that were built, were aligned with existing foundation lines so as to be able to adaptively reuse the already-existent concrete footings.

In terms of renewable energy generation, the roof of the northeastern administrative wing, as well as the northeastern logistics/back-of-house wing have been set aside for photovoltaic arrays. This approximately-1800m2 rooftop space would allow for, at maximum, a 360KW photovoltaic system (assuming 400 watt panels) to be installed. This would generate on average 2800KWh per day.

Common estimates for museum energy consumption is placed around 100KWh for every square meter of museum space. This places the Carthage National Museum’s daily energy consumption to somewhere between 1750-2000KWh per day. This indicates that there is enough renewable energy that can be generated on site for the proposal not only to become net-zero, but effectively net-positive. Assuming the mitigation and building performance factors further reduce expected energy consumption, this becomes all the more feasible a future for Byrsa Hill.

The site is opened up to the surrounding city as much as possible. The museum, the cathedral, and the varying administrative, logistic, and cultural service areas of the proposal can be fully closed during off hours, but the broader site is designed to behave as an active public park—as a series of active urban plazas linking back to the surrounding urban fabric.

Entries to the site that were once closed are opened up, and those that are already active are strengthened. The public plaza spaces adjoining these entry points are shaped to support various activities of socialization, recreation, community engagement, and cultural production.

The entries to the southeast, south, northwest, north, and north are generally for pedestrians. The entry from the west and east are for vehicular traffic. The western entrance leads to UNESCO square, which is designed as a large-scale curbless plaza (shaped around the principles of urban planner Hans Monderman). Here there is even enough space for a bus to drop a group of visitors. The eastern entrance in turn is for logistics / staff. Parking spaces and loading/unloading zones are found there.

With the four illustrations provided, we highlight: the sequence from Foundation Carthage to Punic Carthage (top left), Roman Carthage (top right), the Tophet (bottom left), and the temporary exhibit space (bottom right).

Foundation Carthage to Punic Carthage is housed in the southwestern wing of the museum. This long stretch of space is broken up into three distinct zones accentuated by the new architectural interventions intersecting with this wing. The materials used are rustic, raw, earthen—a language that evolves as we stretch across the epoch. The stands displaying critical archaeological items for instance, go from being rough-hewn, to smoothed, to polished sandstone as we traverse this period. Extra-small and extra-large scale exhibits, digital projections, and interactive spaces are interwoven to shed light on the historico-cultural fabric in an engaging manner.

In Roman Carthage, in the southeast wing, the tone shifts. The red of the Roman paludamentum weaves across this space. Visitors are greeted by thick red walls and a forest of Roman columns, in varying states of completeness or decay. Arrays of small stands once more support the archaeological findings of this era. However, they are now polished, and capped with a strip of red. In a critical corner, the Statue of Ganymede stands out against a sharp black alcove, an illustration of Roman Carthage projected upon the backdrop.

As visitors turns their back to the Statue of Ganymede, the distant view of a cave-like space catches their eye. A brick barrel vault frames a stela, a subtle spotlight illuminating it from above. Passing into this space, the visitors find themselves in the Tophet. Stelae, some big, some small, weigh heavily upon a sea of sand. Subtle spotlights puncture the darkness, highlighting the eclectic array of stones from above.

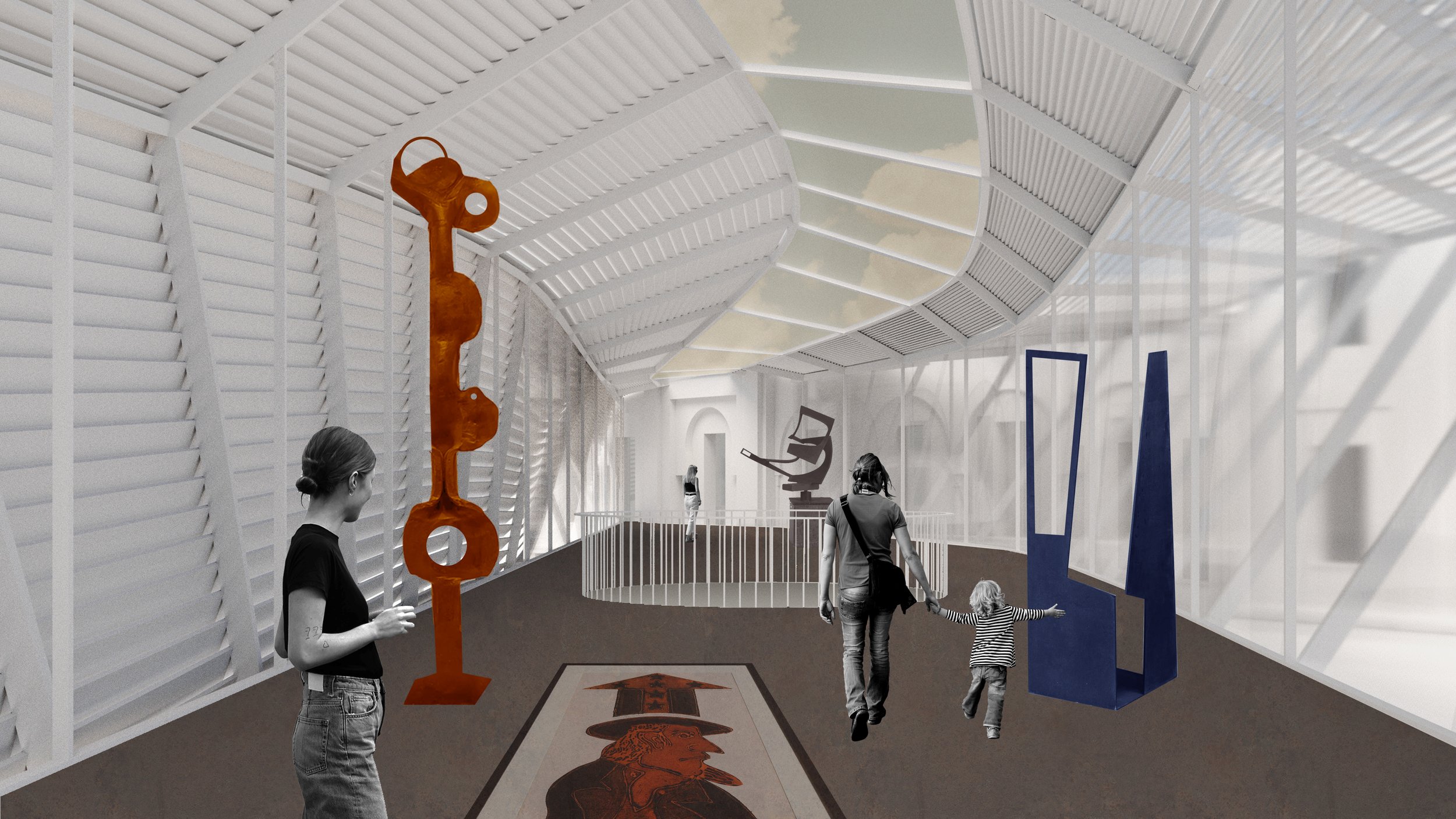

In the temporary exhibit space, the visitor is in the belly of the new intervention. Lines of wood planks form the walls and ceiling, and strips of diffused ribbon windows open up views to the surroundings and the sky. The visitor feels as if they are inside an undulating ship, resting on its back. Designed for temporary exhibits and more-experimental exhibit work from artists-in-residence, the new gallery provides a unique new voice to the scenographic sequence.

Building demolition is kept to a minimum throughout the project, and even in areas of the proposal where no option besides demolition could be found, the footprint of new construction is placed to be able to re-use existing foundations. The new architectural interventions rely on reused steel and wood materials and methods. The structures were simplified so as to avoid digitized customization. Wood in particular was selected in order to help reboot the rather ample lumber industry in Tunisia that is struggling to find a local market. These materials also help to reduce the proposal’s carbon footprint. Beyond these new interventions, the broader construction methodology employed throughout the building relies on fairly conventional brick and concrete techniques and approaches.

Local materials, often ones already in use within the site, are heavily utilized throughout the masterplan. The hardscaping for the landscape design uses white marble-waste and pebble-concrete finishes already visible throughout the site.